Body, Beauty,

and Brokenness

The artist’s reflection on a lifetime of listening, learning, and making

The human body has been the centerpiece of religion, art, and culture from ancient Mesopotamia and Africa to modern Europe and North America. In Western traditions the body of Christ is often depicted as weak and broken — scourged and dying on the Cross or dead and entombed. In that tradition, showing the Savior as weak and broken goes to the heart of a new covenant: God is no longer presented as distant, perfect, unappeasable, unreachable — but as very present to and in solidarity with suffering humans. The idea of a distant Deity pairing its fingernails as humans and animals — nature herself — suffers and groans is gone.

Detail of The Flogging; from the series Golgotha

The brokenness of the Body of God on the Cross is a startling image, especially when combined with authentic faith in a Creator who cares and knows our dilemma. It flies in the face of all human notions of superiority, power, and privilege extended to kings and queens and ruling classes who often justified their power by reference to divine right. Moreover, when the 19th-century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche declared “God is dead” — a philosophic statement comprising much of modern thinking post-Darwin — he may not have realized that he was theologically correct. God did indeed suffer death on the Cross — and some theologians might be even willing to go so far as to say that this “death of God” was quite literal. Yet to leave out the end of the story — the Resurrection of Christ — would entail committing a crucial violence to the narrative.

God suffers and dies alongside of us

Details of ‘Climbing San Miniato’ and ‘Passion’ from the series Building in Ruins

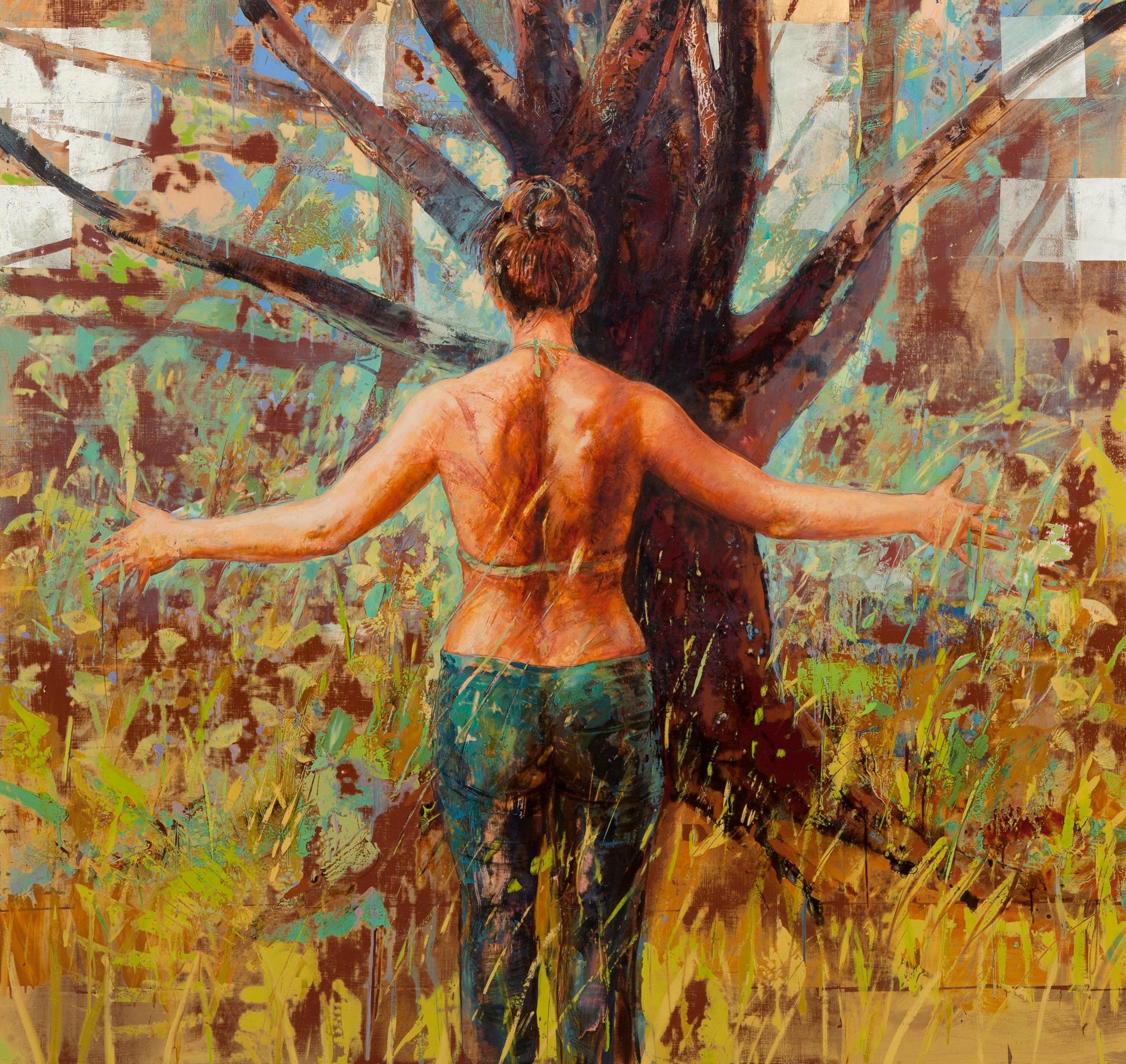

And the resurrection has also had major depictions in the Western tradition. But perhaps more surprising is the beauty released through that suffering and weakness taken on by the God of the Bible — redeeming the seeming meaninglessness of our pain. As an artist I am drawn to the paradox of “power made perfect in weakness” (2 Corinthians 12:9). The imagery that came to me initially in the early 1990’s (in my series Golgotha) was directly based upon the accounts of Good Friday in the Bible. Later, after our house and studio burned in 1997, I began to seek a more allusive approach to imagery of God’s paradoxical broken beauty. Those early attempts post-fire included a group of paintings I called Building in Ruins — indicating both the noun and the verb — a broken house and actively building in-and-with the wreckage. My studio process that involves both the making and the breaking/ruining individual works became a kind of symbol — and all my work undergoes this vigorous losing and finding of the image amid many “ruined” layers.

After our house and studio burned in 1997, I began to seek a more allusive approach to imagery of God’s paradoxical broken beauty

Somehow the reality of our ruined home and studio was stitched together with my earlier artistic imagery, and I saw in the smoldering heap of our house a brightening hope for the future. The Hebrew prophet Isaiah speaks about “good news for the poor” in Isaiah 61: 1-3 and this is the passage Jesus read publicly from the scroll in the synagogue just after he’d begun his ministry and returned from being tested by the devil in the desert. The verses directly following this (Isaiah 61:4 and following) describe the future of a God-renewed civilization:

They will rebuild the ancient ruins

and restore the places long devastated;

they will renew the ruined cities

that have been devastated for generations.

Details of ‘QU4RTETS No.1 - Spring’, ‘QU4RTETS No.2 - Summer’, and ‘QU4RTETS No.4 - Winter’ from the series QU4RTETS

As a painter I find this thrilling and packed with potential imagery for a prophetic and hopeful witness in art. In subsequent bodies of work from 2001 through the present, I have continued to explore these three interwoven themes: beauty, the body, and brokenness. This underlying triad of counterintuitive theological and artistic realities fed me deeply and continues to nourish my imagination. In successive series — The Body Broken (martyrs), Magnificat (Mary, mother of Jesus), Woman, Presence/Absence, QU4RTETS (collaboration with Mako Fujimura and Christopher Theofanidis surrounding Eliot’s Four Quartets), and Ordinary Saints (collaboration with Malcolm Guite and J.A.C. Redford) — I continued to explore the implications of these themes both on formal (purely artistic) and imagistic/symbolic levels.

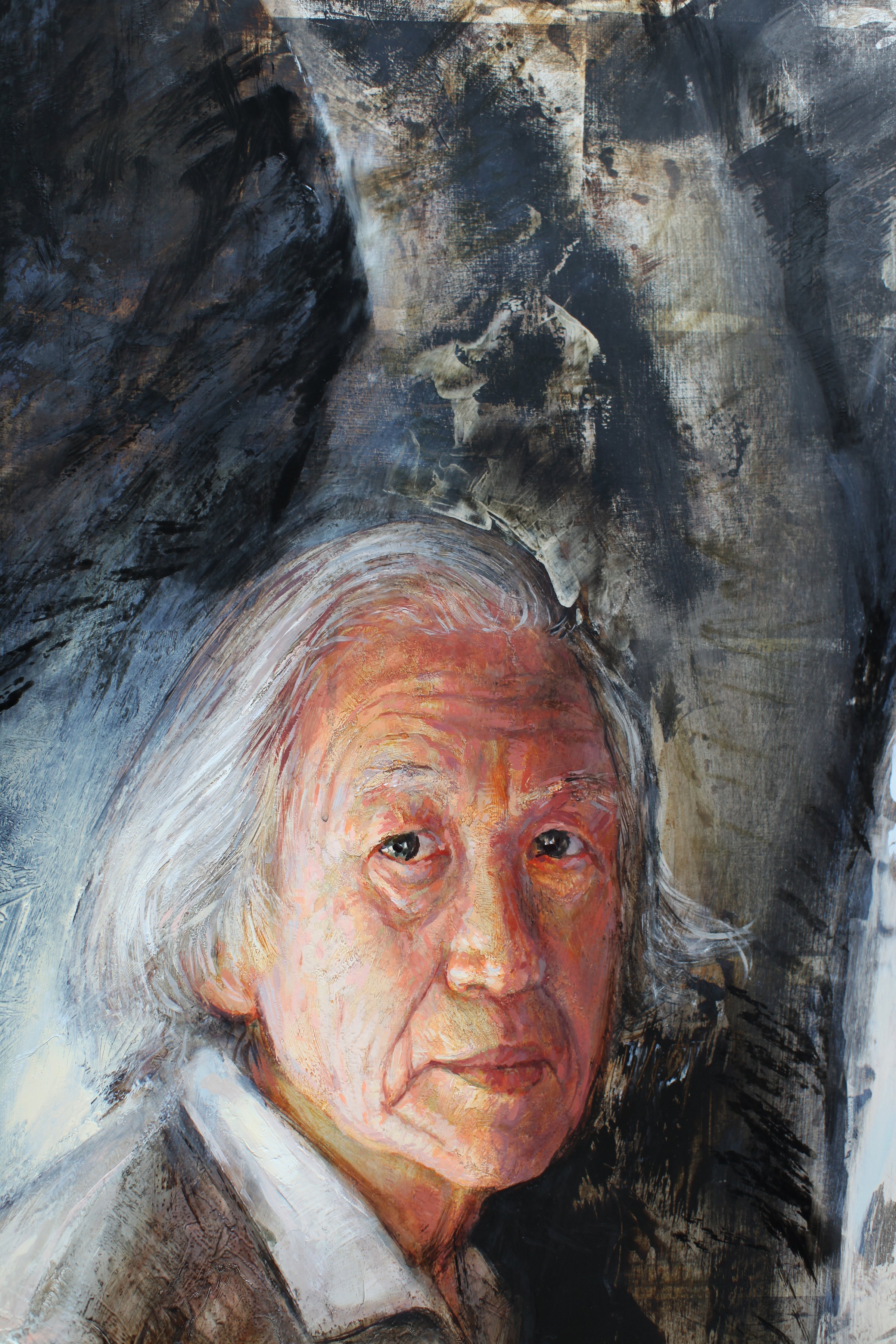

Details of ‘Portrait of the Artist’s Father: William C. Herman’ and ‘Firefly: Mary Herman’ from the series Ordinary Saints

In my current work I continue to develop images of the human form amidst decay and suffering — but I also allow myself extended play with purely formal design elements like color, texture, surface marking, and composition. These purely formal artistic concerns have been fused with the very meaning of my work.

I could even say that the surface of my paintings became deepest aspect of my art and the location of its meaning. Just as we meet a person in their face and in the intimate touch of their skin, I have come to believe that my art is best met and seen on the surfaces that result from my strange methods of making and breaking. It’s as though all the decades of striving and struggling served like photosynthesis serves the flower — becoming the invisible juice feeding the surface, producing the flower of my art. Even though the imagery is still often focused upon the broken or imperfect human form, I find that as I get older, I am more and more drawn to beauty itself as redemptive and hope-filled. Color itself, form itself can communicate without imagery. What we often call “abstract art” can surprisingly be a more direct approach — much like music which doesn’t depict anything, simply generating a feeling through tonality, melody, and musical form.

As I get older, I am more and more drawn to beauty itself as redemptive and hope-filled

So, I find myself free to explore both image and abstraction together — allowing them to fuse and point toward what T. S. Eliot called a “costly simplicity”.

If I were to summarize my intent as a painter in a single sentence it would run something like this: I desire more than anything to meet my viewer and welcome them across the threshold, across the boundary of self and other, into a place of festive hope and unity. I am unembarrassed to speak in such terms because I believe that Christ has done this very thing — welcomed humans across an unbridgeable distance by laying down his life for us, his friends. If my art can give even a dim echo of that mysterious invitation, I can rest as a painter.

— Bruce Herman

•••

RELATED CONTENT